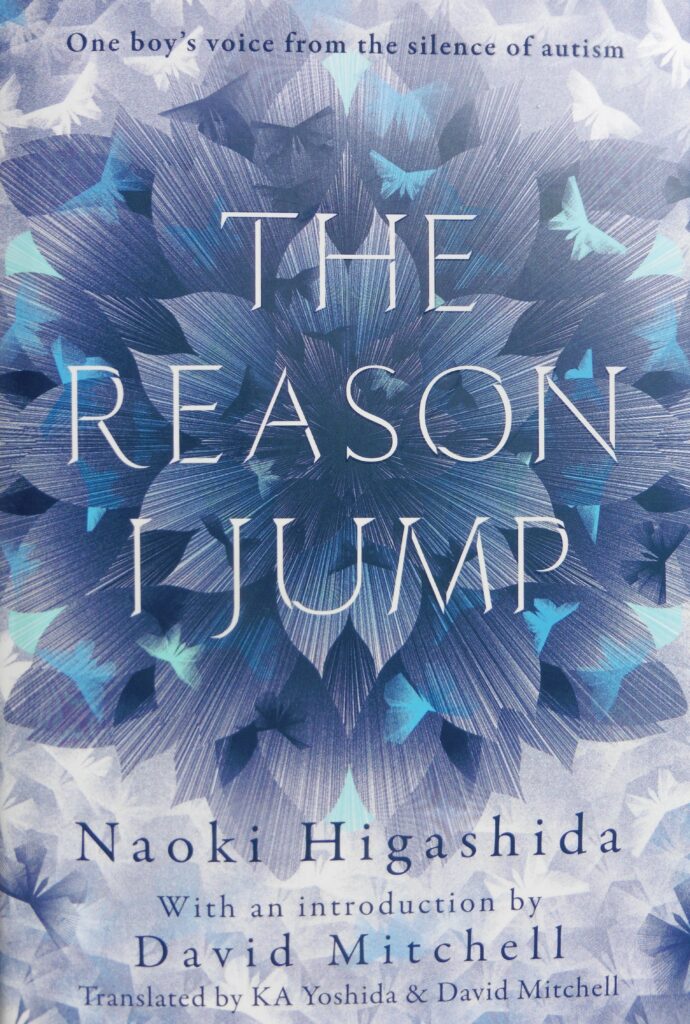

by Naoki Higashide

Translated by KA Yoshida and David Mitchell

Sceptre (Hodder and Stoughton), 2013

If you want a book that will challenge your assumptions about what others are thinking, and thereby increase your empathy, then this is the book for you. It was written by a Japanese 13-year-old boy who only communicates by using an alphabet map, and was translated by two parents of a child with autism. It is structured as a series of questions about some of the behaviours considered to be characteristic of autism, such as:

Why do people with autism often cup their ears?

Do you like adverts on TV?

Why do you wander off from home?

My knowledge of autism is limited, having only observed the behaviour of my friend’s child, but I recognised many of the behavioural traits covered in this book: repeating phrases over and again; running off suddenly; intense anxiety over seemingly small triggers; extraordinary recall and observation skills.

What I hadn’t realised is how many assumptions I was making about the reasons for these behaviours. I had assumed, for example, that suddenly taking off was an impulsive behaviour, or indicated chasing after something particular. Higashida explains that for him, it represents a certain lack of control over his body, almost as if on auto-pilot. I had not considered that it might not be a deliberate action, simply because my body naturally does as it is commanded. The Reason I Jump made me realise that I was trying to understand other people’s behaviour from the standpoint of my own perceptions of the world and of society, which is both wholly inadequate for explaining another’s behaviour, and is, frankly, a somewhat arrogant position.

However, Higashida’s explanations never intend to evoke a sense of pity, and instead detail another viewpoint on reality. He eloquently explains that people with autism may be striving to connect, both with their environment and with other people, despite our perception that people with autism eschew human relationships. Higashida describes life in technicolour, which he sometimes experiences as too loud for his senses, but which inspires awe. It made me realise how often I simply rush past nature, without taking the time to enjoy the miracle of life and nature. Under “Why do you like spinning?”, for example, Higashida expresses the simple bliss of enjoying every moment (p.101):

“Just watching spinning things fills us with a sort of everlasting bliss – for the time we sit watching them, they rotate with perfect regularity. Whatever object we spin, this is always true. Unchanging things are comforting, and there’s something beautiful about that.”

Throughout the book, there is also a deep sense of being one with nature, and the fullness of experience that the neurotypical miss out on (p.123-4):

“But human beings are part of the animal kingdom too, and perhaps us people with autism still have some left-over awareness of this, buried somewhere deep down.”

The Reason I Jump has been translated into thirty languages, and was adapted into a documentary film in 2020. It’s a book that will stay with me a long time, and one I will keep dipping back into, to remind myself sometimes to look at the world from another perspective. It challenges us to take the time to notice the awe-inspiring world that we live in everyday, but don’t fully appreciate. The Reason I Jump is a truly fascinating and thought-provoking window into another person’s reality (p.122):

“We are misunderstood, and we’d give anything if only we could be understood properly […] Please, understand what we really are, and what we’re going through.”